|

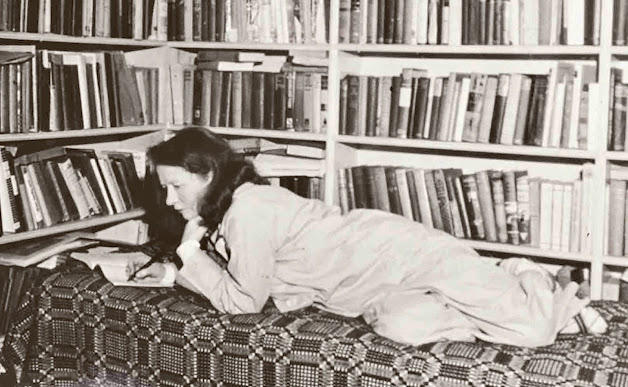

| Edna St. Vincent Millay (circa 1920) |

Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink

Nor slumber nor a roof against the rain;

Nor yet a floating spar to men that sink

And rise and sink and rise and sink again;

Love cannot fill the thickened lung with breath,

Nor clean the blood, nor set the fractured bone;

Yet many a man is making friends with death

Even as I speak, for lack of love alone.

It well may be that in a difficult hour,

Pinned down by pain and moaning for release,

Or nagged by want past resolution's power,

I might be driven to sell your love for peace,

Or trade the memory of this night for food.

It well may be. I do not think I would.

Edna St. Vincent Millay was one of the writers -- along with Whitman and Dylan Thomas -- who drew me to poetry as a teenager. More than 50 years later, I still love and admire her work.

Millay was born in 1892 on the rocky coast of Maine; she and her two sisters were raised by their poverty-stricken mother. (Her middle name came from the New York hospital where her uncle's life was saved shortly before she was born.) She attended Vassar as a scholarship student and published her first collection of poems the year she graduated.

She then moved to New York's Greenwich Village, where she made friends among the writers and artists there and supported herself by writing stories for magazines, under the pen-name Nancy Boyd. Meanwhile, her poems were acquiring a wide readership, based as much on her frank sexuality and feminism as on her skillful writing.

At 31, Millay became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for poetry for The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver. She went on to write many more poetry collections, six verse dramas and the libretto for the opera The King's Henchman. Despite her convictions as a pacifist, she worked tirelessly to support the war against fascism in the 1940s, writing both poetry and propaganda for the cause. Millay died in 1950, at the age of 58, at her home in Austerlitz, New York.

Millay's poetry belongs to English verse traditions that stretch back to Shakespeare, but, like Robert Frost, she infused them with the vital cadence of American speech and a distinctly personal voice. Seldom has any American deployed rhyme so effortlessly: no wonder she was one of Thomas Hardy's favorite poets.

If Millay's work seems too overtly emotional to many 21st-century ears, that loss may be ours. Her best poems seem likely to live as long as English does.